In autumn 2021, Jacob Geersen, currently a marine geologist at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research, led a week-long field course at the University of Kiel. The course took place entirely on a research vessel in the Baltic Sea.

Geersen favors the outdoor classroom environment. "It's quite immersive," he explains, noting that for many students, "it may be the highlight of their academic journey."

During the nightly shifts, students meticulously charted the contours of the seafloor with high precision. Geersen remarks, "Typically, when we conduct these measurements on expeditions, we stumble upon something intriguing." This research voyage was no different.

One evening, amidst the waters of the Bay of Mecklenburg, along the northern coast of Germany, the students activated the echosounders and charted a section of the seabed. "The following day, upon downloading the data," recalls Geersen, "as we reviewed it together, we noticed a peculiar feature on the seafloor. It was something quite remarkable."

Unbeknownst to them at the time, just under 70 feet below the water's surface, they had chanced upon a stone wall stretching over half a mile, dating back to the Stone Age — one of the most ancient megastructures known to humanity. In a study published in PNAS, Geersen and his team suggest that this ancient hunting structure might have been utilized to corral and hunt reindeer, showcasing a level of sophistication among the prehistoric hunter-gatherers who inhabited the area some 10,000 to 11,000 years ago.

The Unveiling of the Blinkerwall

Geersen was accustomed to seeing rocks and stones appearing on the echosounder as irregularities scattered across the floor of the Baltic Sea, remnants of the glaciers that once covered northern Europe millennia ago. Yet, aboard that vessel in the Bay of Mecklenburg, he immediately recognized that what they had stumbled upon was distinct.

"There seemed to be something winding its way through the mapping," describes Geersen. It was a ridge extending for six tenths of a mile. "I suspected that these were likely rocks, arranged one after another," he explains.

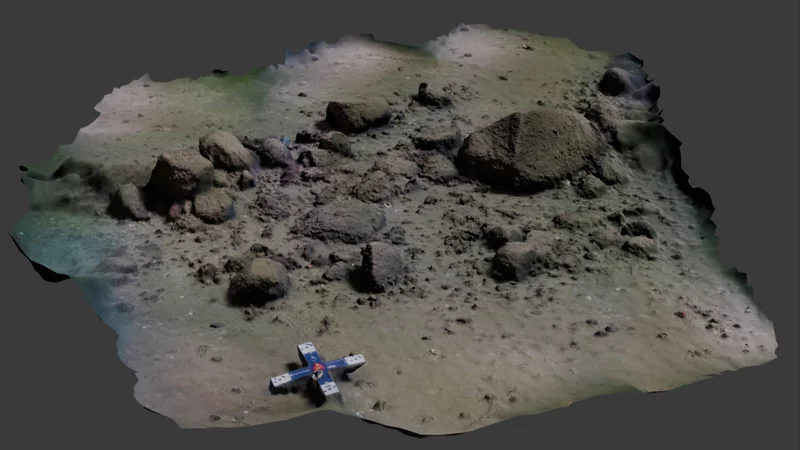

A year later, Geersen, along with his colleagues and a fresh group of students, revisited the same location. They deployed a camera to inspect the area and verified that the ridge consisted of numerous rocks, forming a wall approximately 1.5 feet in height on average.

Geersen explained, "The stones are typically small, like those of tennis or soccer ball size, thus easily movable. However, in certain areas where larger stones are present, the orientation of the wall changes."

Geersen and his team were puzzled by the formation of such a structure, which they named the "Blinkerwall" in reference to a nearby underwater mound known as Blinker Hill. They couldn't comprehend how such a formation could have occurred naturally.

"When we presented our findings to the archaeologists, they acknowledged the potential significance," he remarks.

"Among the team members, I held the most skepticism," recalls Berit Eriksen, a prehistoric archaeologist at the University of Kiel, specializing in the migration patterns of people in northern Europe following the retreat of glaciers after the last Ice Age, spanning 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. Reflecting on her examination of the Bay of Mecklenburg structure, she recalls a quote from Sherlock Holmes: "When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth."

"Archaeologists seldom speak in terms of 'truth,'" Eriksen concedes, "but I find myself running out of natural explanations. That's the challenge I face."

As Eriksen meticulously analyzed the data, her conviction grew that the structure was crafted by prehistoric humans, utilizing numerous smaller stones to interlock with the larger, immovable rocks forming a wall. "I dismiss the notion of UFOs, so the conclusion must be human craftsmanship," she asserts. Eriksen and her fellow archaeologists involved in the project reached a consensus that the wall likely served as a tool for hunter-gatherers approximately 10,000 to 11,000 years ago, aiding in the herding and hunting of reindeer during the Stone Age.

Strategies for Mass Reindeer Hunting in the Stone Age To effectively hunt large numbers of reindeer, ancient hunters devised ingenious methods. "The most viable approach involved herding them towards a concealed shooting spot or blocking their path," explains Eriksen. Reindeer, by instinct, tend to trail along natural barriers, such as sturdy stone walls like the Blinkerwall.

"Beyond the wall, there likely lay a body of water," notes Eriksen. This geographical setup created a bottleneck, forcing the reindeer between the wall and the water, leaving them vulnerable to the waiting hunters' arrows. Eriksen suggests that despite their nomadic lifestyle, these ancient communities may have had established migration routes, possibly revisiting this strategic location annually.

"If one constructs a structure like that," Eriksen suggests, "it signifies a profound understanding of the entire region. It's not merely traversing unfamiliar terrain or relying on chance encounters with reindeer. It involves meticulous planning, foreseeing where the reindeer will be in the following year." This notion has been speculated by archaeologists for some time, and Eriksen believes that this wall adds weight to the hypothesis, suggesting its validity in prehistoric Europe. Eventually, the area succumbed to flooding, giving rise to the Baltic Sea as we know it today, and submerging this particular hunting architecture underwater. Ashley Lemke, an underwater archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, although not directly involved in the study, praised the research for its robustness, especially considering the challenging conditions under which it was conducted. "From personal experience, I can attest that working underwater is no easy task," says Lemke, who has uncovered similar stone structures in Lake Huron, one of the Great Lakes adjacent to Michigan. Lemke elucidates that these findings underscore the argument that people during the Stone Age possessed a sophistication and complexity that is often underestimated. "We often imagine them teetering on the edge of starvation, eking out a living from the land. But that's simply not accurate," she asserts. Instead, "people in Europe were constructing monuments before the likes of Stonehenge, preceding the emergence of these more recognizable classical structures."

"This represents some of the earliest instances of what could be considered animal domestication," Lemke elaborates. "Prior to establishing permanent animal pens, there was a practice of constructing fences for hunting purposes, which I find particularly intriguing." This early form of animal control might have paved the way for the eventual development of livestock herding.

To validate whether the wall was indeed constructed by prehistoric people for hunting, further archaeological evidence of hunting-related activities is necessary, as noted by Berit Eriksen. Given that hunters would have needed to wait for reindeer to appear, Eriksen suggests that traces such as small charcoal fragments could indicate the presence of humans who would have needed to cook and eat during their wait. Excavations could potentially uncover arrowheads or ancient DNA. Furthermore, Eriksen adds, "They would have also left behind bodily waste, so with some luck, traces of human activity could be found."